In the early 2000s, engineers, designers, and creativists were obsessing over the immediate, printable future. They would use open source to build 3D printers and throw buzzwords like changing humanity around. The big idea was 3D printing (a collection of processes where layers of material is joined to create a three-dimensional object from a digital file) and depending on what one was reading, it either felt futile or as if the future was hidden in a cartridge.

Once the market saw smaller and reliable 3D printers, media gobbled the innovation and optimistically shared the following analogy: Remember how everyone thought computers would only be used by nerds but then they were splashed around and blinking in almost every home? 3D printers, too, would be the next computers, the next microwaves, or the next-anything found in every modern home.

But nearly two decades later, that future is still evasive.

Innovators like Bree Pettis of Makerbot Printers – the first company to sell the vision of desktop 3D printers – have moved on, and a range of analysts have dissected their trajectory to conclude the one monumental mistake they made: the market for 3D printers is businesses and colleges, not individuals. Not yet.

But as Makerbot was hoarding desk and mindspace, hoping you’d buy a 3D printer, a new Massachusetts-based startup, Formlabs was getting ready for launch.

Formlabs 3D Printers (PC: Formlabs Facebook Page)

Started in 2011 by three MIT engineers and designers, this 3D printing company seems to have got something right.

With a roster of clients such as Sony, Google, the Harvard University, and others, the company has, first and foremost, aptly positioned itself as a 3D printing solution for “professionals”. Last month, it raised $30 million in a Series C funding led by Tyche Partners, which puts its total funding north of $85 million.

Formlabs’ secret? It’s a little technical. Startups before Formlabs used the FDM technology which builds parts layer-by-layer by heating and throwing out something called thermoplastic filament. Formlabs is credited as the first company to launch smaller, more affordable 3D printers using the stereolithography or SLA technology.

What the SLA technology does is that it converts liquid resin (used as cartridge) into solid parts, layer by layer, by selectively curing them using a light source in a process called photopolymerization. SLA is more effective than FDM in creating intricate designs and is used to create models or prototypes for dentistry, jewelry, toys, footwear, education, among others.

Once the three MIT students: Maxim Lobovsky, Natan Linder, and David Cranor envisioned this, they raised money for their first SLA-based Form 1 3D printer through a Kickstarter campaign. People were clearly in the future-hidden-in-cartridge camp as the campaign raised a record breaking $2.95 million and made the Form 1 one of the most highly funded projects of all time.

Since then, the company has gone on to build faster and more reliable printers such as Form 1+, Form 2, Fuse 1, and an industrial system called Form Cell. The Form 2, its most popular product, costs more than $3,000.

3D Printing For All

For the ideological and prescient 3D printing community, this technology is not about printing trinkets and plastic action figures, but building things that reduce your trips to the store and more importantly, bring value. Formlabs, too, sees 3D printing as the future of customisation and a challenger to mass production.

For example, one of Formlab’s clients is Egf Manufacturur, a German wedding ring manufacturer, that uses the startup’s Form 2 desktop 3D printer. They configure a wedding ring in CAD software, print it in 3D, and give it to the customer before the ring is hand-crafted by the goldsmith. Reportedly, Formlabs CEO Max Lobovsky also proposed to his fiancée through a 3D printed ring.

A 3D printed: Before and after (PC: Formlabs Facebook Page)

But from knowing how to 3D design to ensuring that the printer works smoothly without getting jammed or spewing out a crooked product, mass adoption of 3D printing is laden with challenges. For Egf Manufacturur, the Formlabs blog says, “The company customized their CAD software (A 3D printing design software) so that employees, seated next to the prospective customer, can easily make adjustments to pre-loaded engagement ring designs without formal CAD training.”

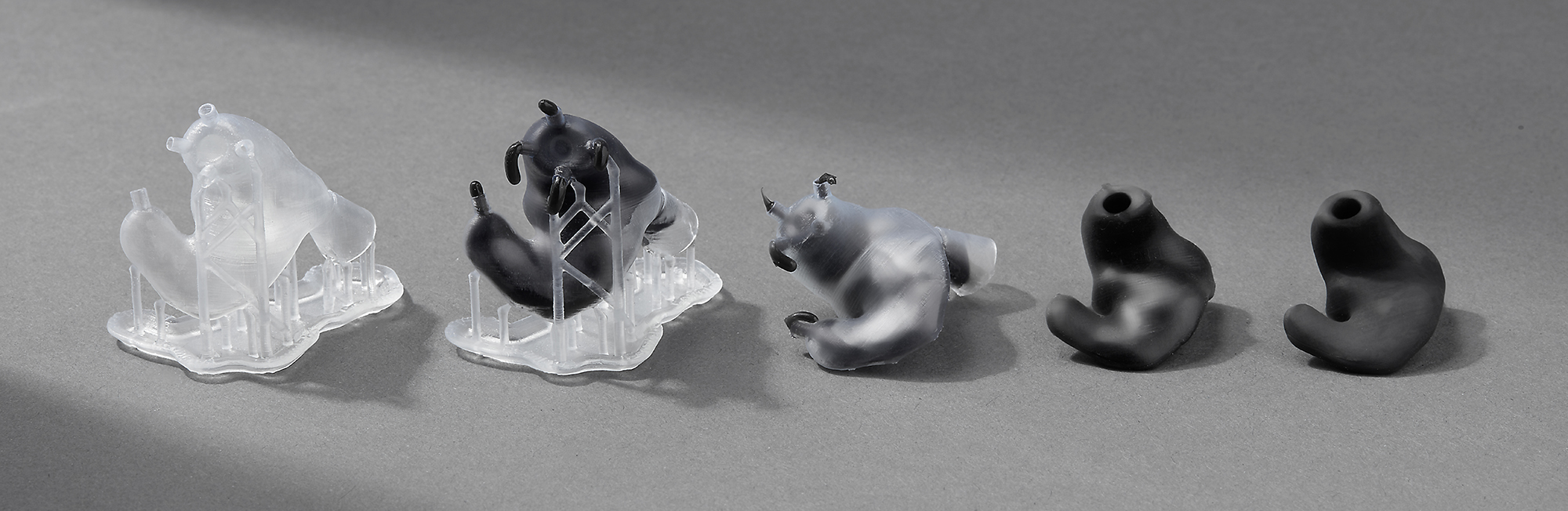

In another example, Formlabs has used the SLA technology to build custom earbuds. Formlab’s blog explains that a technician uses a 3D scanner to take a quick, non-intrusive digital scan your ear canal. S/he then edits the digital file into a 3D printable mold, and sends it wirelessly to the 3D printer. Once printed, the 3D printed shell is removed, and final finishing and coating is done on the final product.

Custom earbuds are made by casting a biocompatible silicone in hollow molds printed in Formlabs Clear Resin. Each printed mold costs $0.40 to $0.60 in resin, and the overall production of a final pair of earbuds costs approximately $3 to $4 in raw materials (including silicone and lacquer). (PC & Caption: Formlabs)

Clearly, 3D printing has multiple uses. Apart from previously mentioned dentistry, jewelry, or audiology, 3D printing is used to build toys, eyeglass frames, footwear, or a range of prototypes as per industry requirements. Architects, for example, use the printed model to internally assess and communicate with clients. Similar processes are applied in varied industries that use 3D printers to print individual parts: Deutsche Bahn, for example, finds it difficult to manufacture parts of its 40-50 year-old trains, so it relies on 3D printers, as does General Electric.

However, 3D printers, like existing smart home appliances, are still not considered revolutionary. The reason is that printers may be smaller, speedier, and more reliable than before; they may also use far less labour, but 3D printing is not very simple. It’s not just a push of a button. It involves high printer and cartridge costs and an ample amount of tinkering and designing.

But with companies like Formlabs in the lead, there’s enough chatter about custom production as the future of 3D printing. Every once in a while, the discussion is also backed by studies. Like a recent ING Think report which notes: “Tentative calculations show that, if the current growth of investment in 3D printers continues, 50% of manufactured goods will be printed in 2060.”

In a wholly different way since the Gutenberg press, the future might just be printable.

Subscribe to our newsletter